Many different statistical regimes are used in hypothesis testing, and it can be easy to get lost in the array of choices. Although it’s easy to find zealots arguing that one approach is universally better (also known as the “statistics wars”), every statistical method has unique strengths and weaknesses. The wide range of nuance in data analysis means that any of them may be most suited for your particular use case.

While there are many resources comparing statistical regimes, they tend to focus solely on statistical power. In this post, we argue that a more holistic comparison is beneficial, and analyze the five common statistical techniques along multiple dimensions (statistical power, intuitiveness, flexibility, robustness, and ease of implementation) in order to help you pick which methodology is the best fit for your use case.

This article was originally published on Eppo’s Outperform.

How we compared statistical approaches

In order to graphically compare these different statistical methods, we’ll evaluate them on a few key criteria:

Statistical Power

Statistical power quantifies how sensitive a method is to picking up differences in outcomes if they exist. Using a formal definition, it is difficult to avoid apples to oranges comparisons. Instead, when we refer to “statistical power,” we mean it more broadly: how much data must be collected to reach a particular specificity? An alternative way to think about power: if you run an experiment for X amount of time, how narrow are the confidence intervals (or credible intervals) at its conclusion?

For a deeper dive into comparing statistical power, Mårten Schultzberg and Sebastian Ankargren have written an excellent article.

Flexibility

Flexibility in this case refers to how well a method is able to adapt on the fly as more data becomes available. For example, if you realize the effect size might be bigger or smaller than you initially had anticipated, can you adjust the experiment’s runtime, or do you have to start from scratch?

Simplicity

This factor could also be described as the comprehensibility of the statistical method and its usage to a general audience. Proponents of Bayesian analysis, for instance, often prefer it for its intuitive definitions and explanations. Intuition covers both the ease (or difficulty) of setting up and running an experiment confidently (i.e., do you need an intimate understanding of statistics to use this method well?) and the ease of explaining the outcomes and results of your experiment to less-technical stakeholders.

Implementation

This factor refers to the technical effort required to run and analyze experiments using the method. Is it possible to quickly implement a particular statistical test? Are there standard packages available in popular programming languages? Does the approach scale well when analyzing many metrics and experiments?

Robustness

Finally, we look at robustness. Every statistical methodology is built upon assumptions that ensure validity. However, in practice, it is not always possible to guarantee that these assumptions hold. Robust methods can handle (small) violations in assumptions without completely changing the results. Some examples of assumptions that are often made when analyzing experiments:

- Normality of errors

- Multiple observations per user aggregated across time

- Non-stationarity across time

Comparing The Methodologies

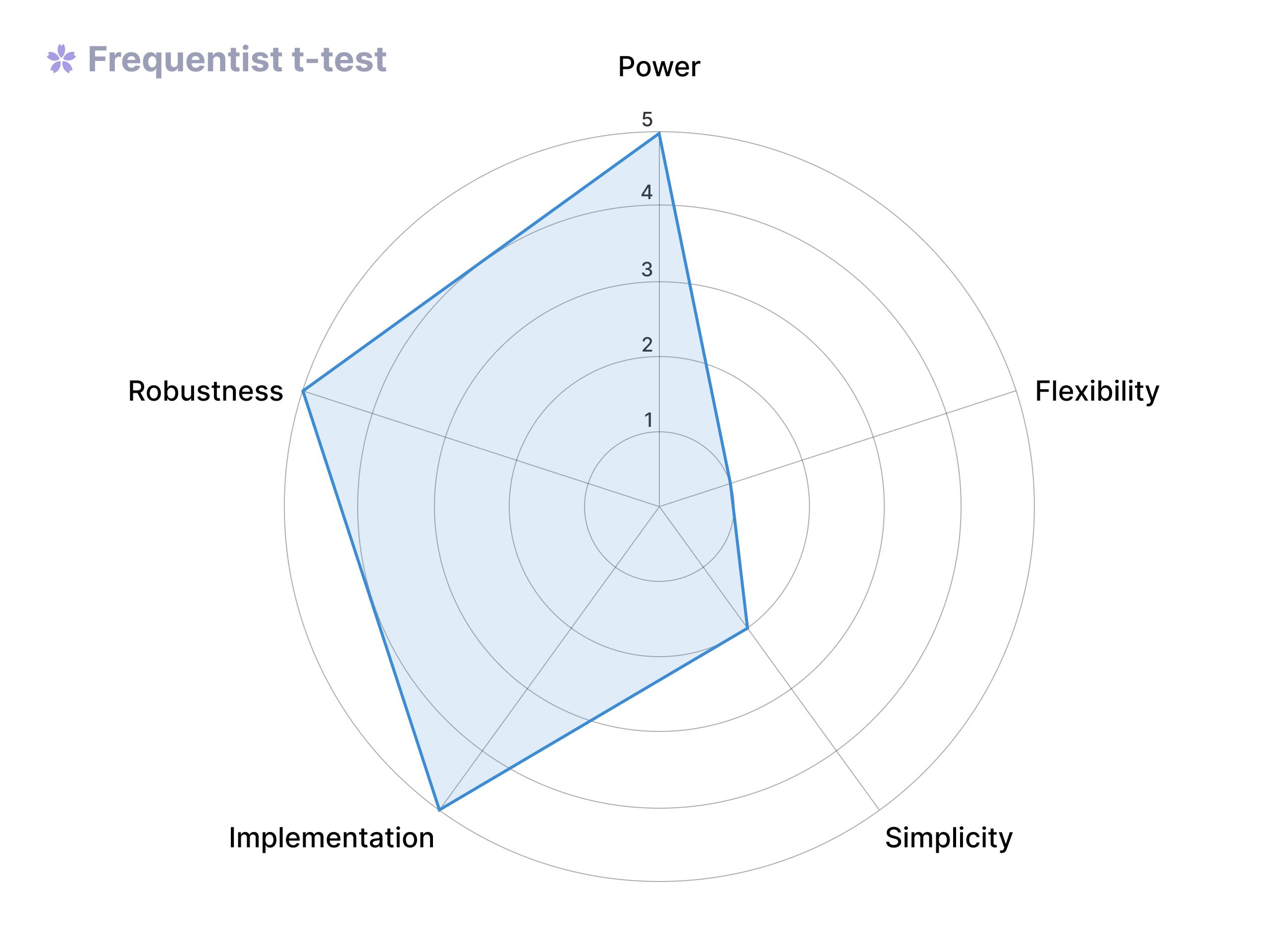

Frequentist t-test

Hypothesis testing has a long and storied history, dating back to the classical t-test often taught in introductory statistics courses. This foundational method is the result of the combined work of Fisher, Neyman, and Pearson. In the classical t-test, you decide how much data to gather ahead of time (e.g., using a sample size calculator), then wait for all the results to come in before looking at the outcome to make a decision.

Pros of frequentist t-tests

- Achieves tight confidence intervals at the end of the experiment, resulting in high power to detect smaller effects.

- Strong and robust statistical guarantees; it is difficult to break the central limit theorem.

- Simplest to implement

Cons of frequentist t-tests

- Pitfalls like peeking may invalidate results, especially for less statistically savvy users

- Only valid with a pre-determined sample size; peeking is not allowed

- Choosing sample size in practice can be difficult as the effect size is unknown ahead of time

When to use the frequentist approach

- When we have very large samples. If we are operating at a scale where runtime is fixed (e.g., at a week or two), and we select the fraction of users to enroll in an experiment to be powered at that fixed runtime — think of organizations on the scale of Meta

- When we care about specific knowledge over the basic decision (i.e., if we care about having the best possible understanding of the actual effect size, we will want to have the tightest confidence intervals possible at the end of our experiment)

- When we can decently predict expected effect sizes (e.g., you have run similar experiments previously), since we need to choose a Minimum Detectable Effect to calculate your sample size

- When all teams involved in the experiment have the knowledge and discipline to not peek at the experiment or act early before the fixed sample size has been reached

Sequential testing

In the 1950s, sequential tests began to gain popularity, particularly in the medical field. One reason is that they allow for adaptability to the effect size being studied. For example, if there is uncertainty about how effective a drug is, a cure rate of 80% could be easy to detect quickly, but we wouldn’t want to discard smaller effects. Even if a drug is only effective for 20% of cases, that may still be very important for an otherwise incurable disease, but it would take much longer to detect. It would be unethical to continue providing patients with a placebo when we know a drug is effective. However, we also do not want to conduct the experiment with too short a duration, as this would result in reduced statistical power and make it difficult to detect smaller yet clinically relevant effects.

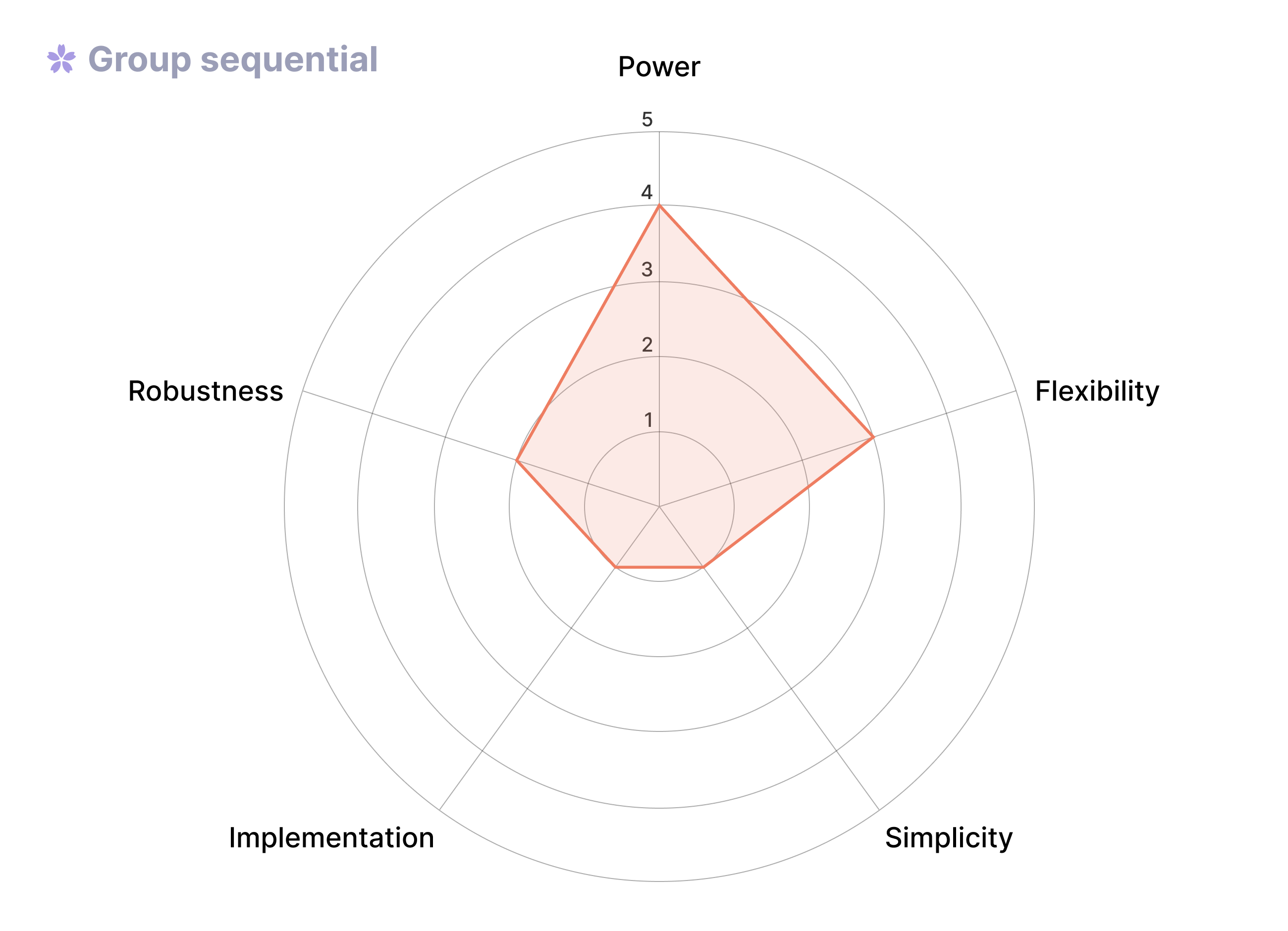

Group sequential tests

Group sequential testing plans for experimenters to make a number of interim analyses, or “peeks,” which are fixed in advance in both quantity and frequency. Group sequential tests have become particularly popular in the medical field and have also recently seen a surge of interest in industry, particularly at Spotify and Booking.com.

Pros of group sequential tests

- Allows for early stopping of experiments if effect sizes are large enough

- Leads to relatively tight confidence intervals by limiting the number of peeks, resulting in the highest-powered version of sequential tests

Cons of group sequential tests

- Hard to implement and code, with few open source available packages (recently Spotify released the Confidence package for Python, which includes a group sequential implementation ported from R)

- More work to do in advance of running the experiment since we now also need to select how and when to peek ahead of time The limited number of peeks may lead to a confusing user experience for teams following along (e.g., when results only update once a week) Relies on strong assumptions (iid observations, stationarity) that often do not hold in practice (more on this on the Spotify engineering blog).

When to use group sequential

- For experienced teams who want to leverage an optimal sequential test and don’t need to worry about impatience from stakeholders if peeks are only planned e.g. every week

- Important (or costly) experiments that are under the supervision of a highly trained statistician (that is why they are so common for clinical trials). In this case, you value the extra flexibility to stop early compared to the t-test, and do not mind the additional complexity.

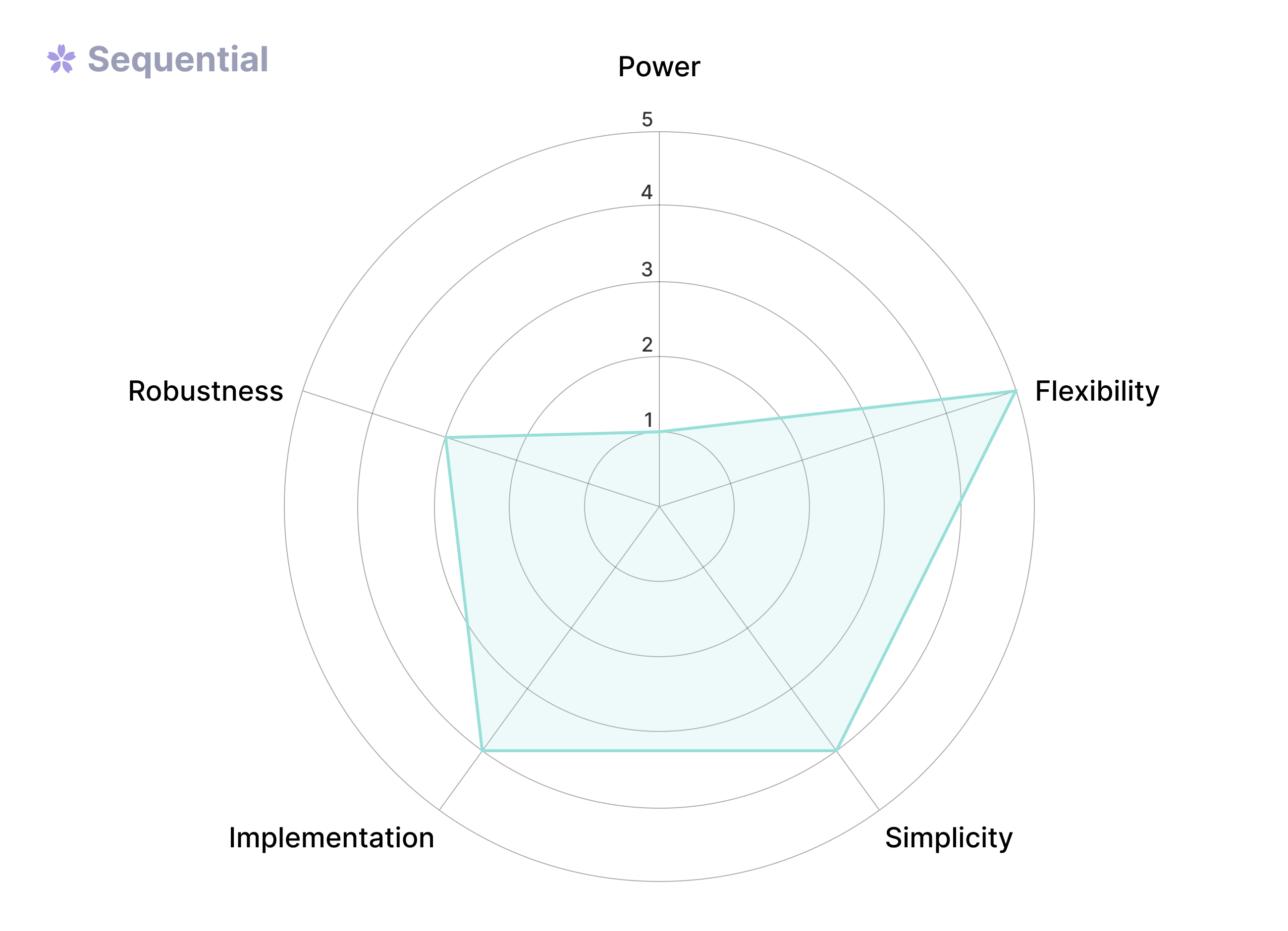

Fully sequential tests

Fully sequential testing, on the other hand, allows the experimenter to stop at any point – no need to pre-determine your cadence and number of peeks. This method has gained more popularity in tech circles in recent years due to the data revolution, as we can now collect data continuously.

Pros of sequential tests

- Easy to set up, easy to use, and requires little oversight to run at scale

- The statistical guarantee is quite robust: it is not easy to break guarantees

- Most flexible: can end experiments early or decide to run the experiment longer

- No need to rely on a power calculation

- Can quickly detect large deviations in a metric (in both positive and negative directions)

Cons of sequential tests

- Experiment runtime is worse when there is a small effect or no effect at all

- Related to the point above, the confidence intervals at the end of an experiment are quite a bit wider compared to alternatives.

- While confidence intervals are always valid, the point estimates of early stopped experiments are more biased. This makes sequential tests less appropriate when the main goal is to learn about effect sizes versus making a decision quickly.

When to use sequential tests

Fully sequential methods are a good default when scaling up experimentation across teams less experienced with statistical analysis. There are no prerequisites to designing each incremental experiment, and the linear progress of the p-value makes it nearly impossible to misinterpret. It is also good at making fast ship/no-ship decisions with good statistical guarantees. That is, when making a quick decision is more important than understanding the precise impact. In this sense, it is the opposite of the classical t-test.

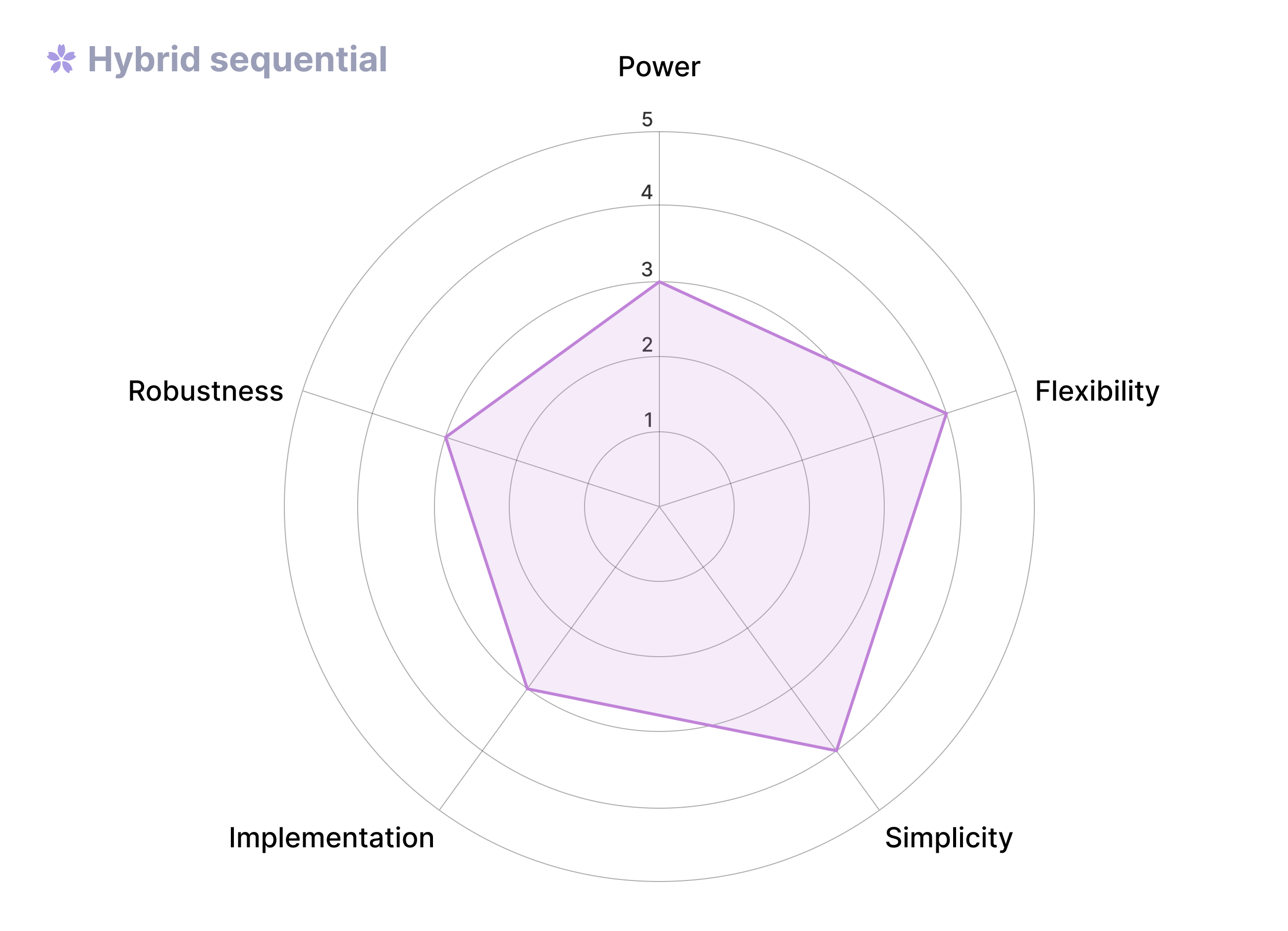

Hybrid sequential tests

Because sequential tests generate a sequence of tests (or confidence intervals), rather than a single one in the case of a t-test, there is no single optimal “boundary” along the sequence. Instead, the experimenter has to choose where to concentrate statistical power. Particular choices for group sequential tests carry names, such as the O’Brien-Fleming test and Pocock test, while fully sequential methods usually have hyper-parameters one can set. More custom forms of customization are also possible. For example, it is possible to combine a fully sequential test during the experiment with a t-test at the end of the experiment period, using $\alpha/2$ as the significance level for each. This combines the best of both worlds, while a union bound shows that statistical guarantees are still met. We call this the hybrid sequential method.

Pros of hybrid sequential tests

- Achieves confidence intervals at the end of the experiment that are almost as tight as those generated by the fixed test, resulting in much high power to detect smaller effects compared to the fully sequential test

- Can stop experiments quickly when there are large effects (either increases or decreases).

- Overall, this provides a balance of strong statistical power at the end of the experiment while still allowing the user to safely peek during the experiment

Cons of hybrid sequential tests

- Like a frequentist t-test, requires specifying experiment runtime ahead of time

- Early stopping still leads to an increase in the bias of point estimates, similar to the fully sequential test.

- Some use cases for hybrid approaches are more specific: Ronny Kohavi, for instance, suggests performing one-sided tests for negative outcomes sequentially, allowing for early stopping in cases of bugs or large degradations (when the point estimate is of less interest anyways)

- It may be confusing when observed confidence intervals suddenly switch to a tighter confidence interval at the end of the experiment

When to use hybrid sequential tests

When you want to combine the benefits from the fixed t-test approach (namely, power at the end of an experiment) and sequential approach (namely, early stopping).

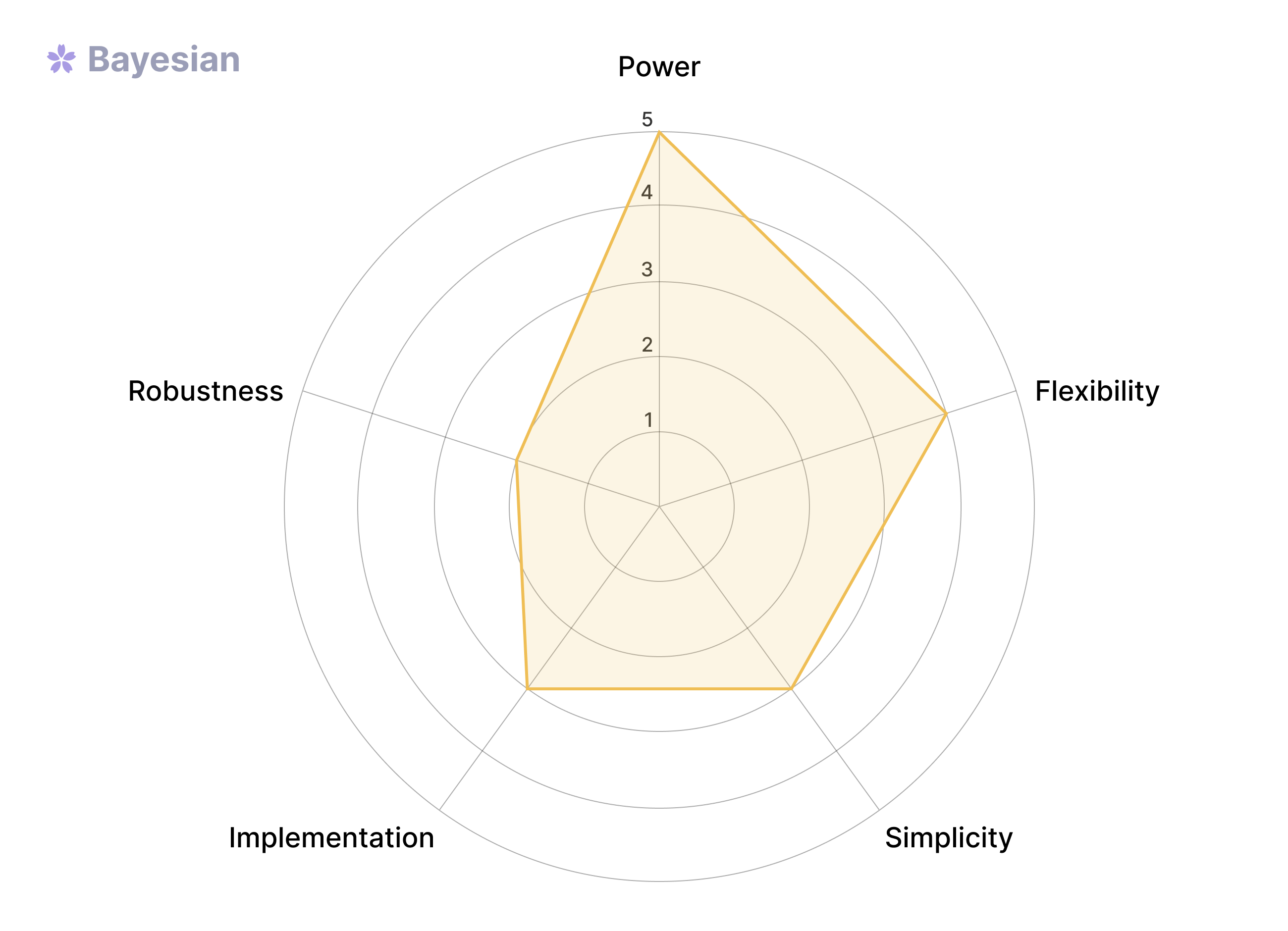

Bayesian analysis

Finally, there is the Bayesian standpoint on experimentation. While all the above methods are frequentist in nature, Bayesian hypothesis testing involves forming a prior belief and then updating it with data to create a posterior. This approach can be difficult to compare with frequentist methods, as the underlying philosophy is quite different. Whether you like or dislike Bayesian methodology is mostly a matter of taste (debates on frequentist vs. Bayesian epistemology and intuitiveness are a common manifestation of this).

Pros of Bayesian tests

- Can explain results in more intuitive language. Even academics often define the frequentist p-value incorrectly, and many business stakeholders prefer the intuitive “chance to be best” (or similar) conditional probability that Bayesian analysis seeks to define.

- Utilizing a prior distribution helps shrink estimates and ease problems with peeking, winner’s curse effects, and multiple testing.

Cons of Bayesian tests

- Statistical guarantees are not as clearly defined and strongly depend on the appropriateness of the prior

- Selecting an appropriate prior can be difficult and is less accessible to non-experts in Bayesian statistics

- Can be more challenging to implement and compute at scale for more complex models.

When to use Bayesian tests

Whether to use a frequentist or Bayesian approach often boils down to preference, but here are some other subjective reasons:

- When you have documented experience running many comparable experiments and can use that empirical data to set appropriate priors

- If you prefer having the ease of explaining results over the rigor of strong statistical guarantees

- In small sample setting (regularizes effects, avoids underpowered analysis) — an important note on one misinterpretation of this benefit: Bayesian statistics does not make it easier to detect effects in small sample sizes, rather it protects you from thinking you have a big effect in small sample sizes when in fact there is none. Note also that in this case using an appropriate prior is even more important.

Conclusion

As is often the case in both statistics and life more generally, there is no silver bullet when it comes to selecting frequentist vs. Bayesian vs. sequential statistical methodology for analyzing your experiment results. Which method is most appropriate depends both on the specific situation and is partially a matter of preference.

Interestingly, the choice to utilize any one of the methods on this list relies not just on the technical context of what is being tested and how your experiment is implemented, but also on the experimentation culture of the team running and monitoring experiments. The experience level of the experimenters and other stakeholders, familiarity with the definitions of key terms, and even basic preferences may make any of these methods more or less appropriate.

For experimentation to drive stronger decision-making, tests must be both run and communicated well. These are challenges we’ve thought a lot about when designing the UI of Eppo’s experiment results and reports for each statistical method. If non-statisticians struggle to look at and understand the results, it will be tricky to grow an experimentation culture – regardless of how optimal your method is.