After two long and rewarding days, CODE 2022 is a wrap. Here’s a biased look at some of my personal highlights; Keep in mind that this is far from a complete list: the conference was filled with quality content and due to the parallel nature of the talks, I missed more than half of them to begin with.

Note: the plenary talks should be posted on Youtube in the next few weeks, at which point I will update this post with links. The figures used in this post are taken from the published work by the respective authors.

Jake Hoffman on the effects of UX on understanding of uncertainty

Jake Hoffman kicked off the conference with an important and often undervalued aspect of experimentation: the user interface really matters. Starting from the “inference” versus “prediction” views popularized by Breiman, he showed that even expert’s interpretation of effectiveness of a drug in an experiment depends a lot on whether one uses standard error of the mean (underestimates variability and hence leans effective) or the standard deviation of the sample (leans ineffective).

It is an important reminder that while we tend to nerd out on the mathematical problems, we cannot forget about the user experience; we need to make sure results are accessible and empower everyone to make good decisions, not only those with a PhD in Statistics.

Interference

It’s clear that interference is clearly one of the most important open issues in experimentation, and more and more people realize how it is affecting their experiments. For those less acquainted with this problem: interference occurs when treatment of one subject in the experiment affects outcomes of other subjects, for example due to a network structure (video chat is only valuable if your friends also have video chat) or a two-sided market (if you book a room, then it is no longer available for someone else). The good news is that there is a lot of exciting research happening in this area.

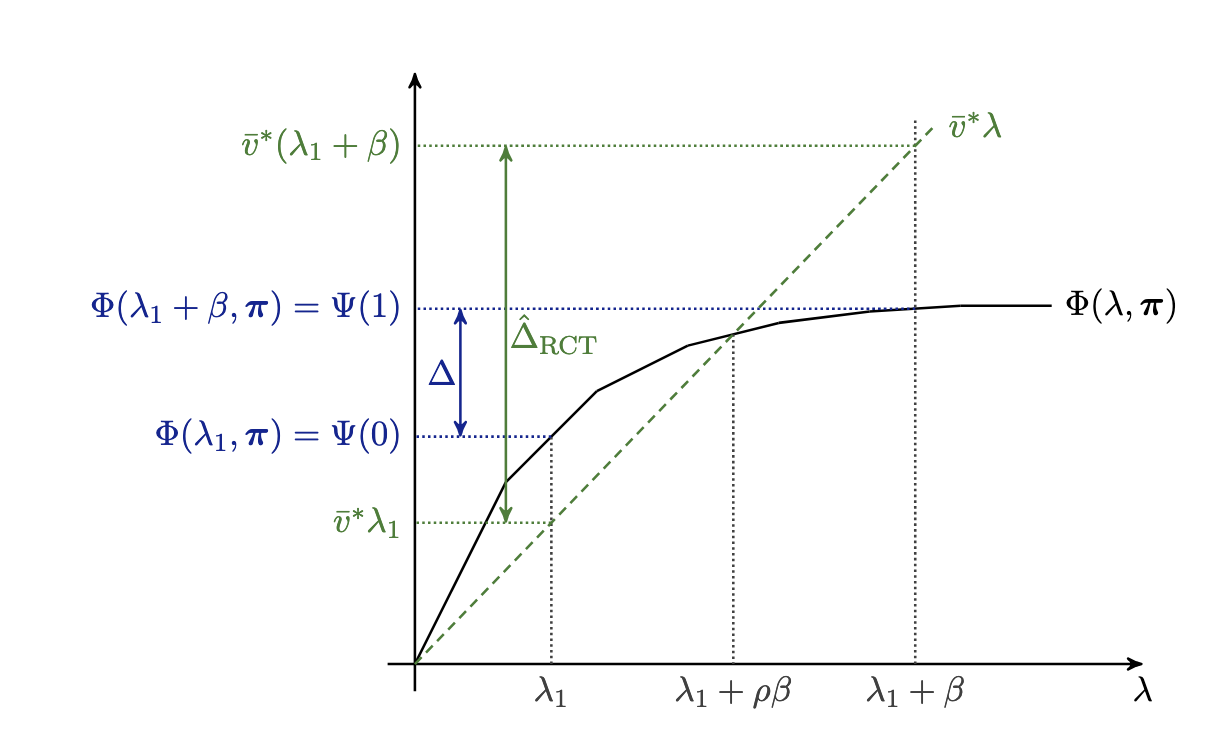

Ilan Lobel on leveraging shadow prices

Interference can take many forms, and is often difficult to model. However, Ilan Lobel argues that the problem can be cleanly modeled in matching markets where a platform has strong control over the matching process (think Uber/Lyft). Namely, the shadow prices of the optimization problem can be used to correct for the bias introduced A beautiful linearization argument both shows the issue from using naive estimation of the average treatment effect (HTE) and how shadow prices address this.

At Stitch Fix I worked on both improving matches between clients and inventory using shadow prices, and on correcting for interference in the experiments we ran, but we never realized the connection.

The full paper is on Arxiv.

Kris Ferreira on human algorithm collaboration

In a fantastic plenary talk, Kris Fereirra discussed her quest to understand how decision makers are interacting with algorithms to make better decisions, and what pitfalls they fall into. By decomposing information into a public part, accessible by both decision maker and algorithm, and private part, only accessible to decision maker, she shows that decision makers struggle to understand when the algorithm provides strong predictions versus when they should rely on important private information to overrule the suggestions by the algorithm.

Instead, decision makers tend to use a convex combination of their own prediction and the algorithm’s suggestion independent of the quality of the quality of the algorithm’s prediction on a particular task. This leads to suboptimal decision both when the algorithm is correct as well as when it is wrong.

There is clearly growing interest in understanding human-algorithm interaction, and I am curious to see how this area develops in the coming years.

Kelly Pisane on unbiased impact estimation

High on my list of best talks was Kelly Pisane from Booking.com She discussed how to go about obtaining unbiased impact estimates from statistical significant experiment results. The talk stands out because it demonstrates clearly that sometimes simple and practical suggestions trumpet complex mathematical modeling.

Every experiment platform faces a post-selection bias problem: statistically significant effect estimates have an upward bias, but it is difficult to understand the magnitude of this bias. Rather than trying to correct for this mathematically, we can do the following: after making a decision, split the remaining users in the control group and use data from that “experiment” to get unbiased estimates of the treatment effect. We avoid the issue that users may already have been exposed to the winning treatment. Furthermore, it often takes some time for engineers to roll out the winner anyway, so you might as well run this second, impact, experiment. Even if you are underpowered to understand the impact of a single experiment, the data can still be used in aggregate across experiments to understand the true impact of experiments. Clever indeed!

Sequential testing

There is clearly a lot of momentum in both academia and industry on sequential testing, with an entire session dedicated to it at the conference. If you are less familiar with sequential testing: unlike classical frequentist methods, this methodology allows for continuous monitoring and adaptive decision making with strong statistical guarantees.

Netflix is heavily invested in sequential testing, with multiple talks, but also Microsoft and Adobe are adopting the sequential paradigm. That said, the sequential framework has pros and cons and does not fit every use case. It will be very interesting to see how this space develops in the coming years

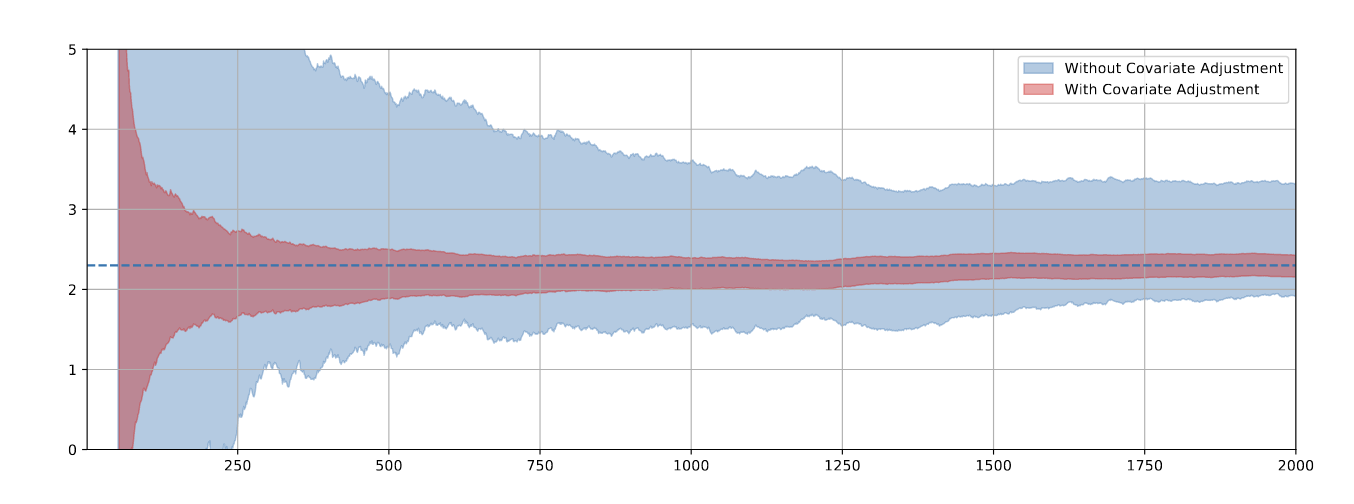

Michael Lindon on sequential testing procedures for regression

It is hard to pick a particular talk from a session full of great content, but personally I really enjoyed Michael’s talk on extending sequential procedures for regressions; this enables us to combine sequential analysis with pre-experiment covariates and linear regression to reduce variance and thus speed up experiments.

Two aspects of this talk stood out to me in particular.

- It is often easy for research to lean theoretical, but here the practical use case is extremely obvious: adjusting for pre-experiment data often speeds up experiments substantially.

- The approach by Netflix is similar but also quite distinct from the way we at Eppo model this problem.

The latter is indicative of a broader phenomenon that stood out at the conference: we all have different approaches to the same problems and that makes it particular valuable to come together and be inspired by each other’s work.

Finally, worth mentioning is the call out by James McQueen that in practice it is very rare to observe a single outcome per user. Instead, we observe a sequence of events from which we construct an outcome that evolves over the duration of an experiment, but this often gets ignored in theoretical work on experimentation. Having struggled with this myself, it is great to see this problem being more broadly.

The full paper is on Arxiv.

Hamsa Bastani on COVID prevention in Greece using Bandits

When it comes to bandits, everyone seems to agree on two things:

- They are beautiful to study from a theoretical standpoint

- But in practice they are not used all that much due to a variety of complications

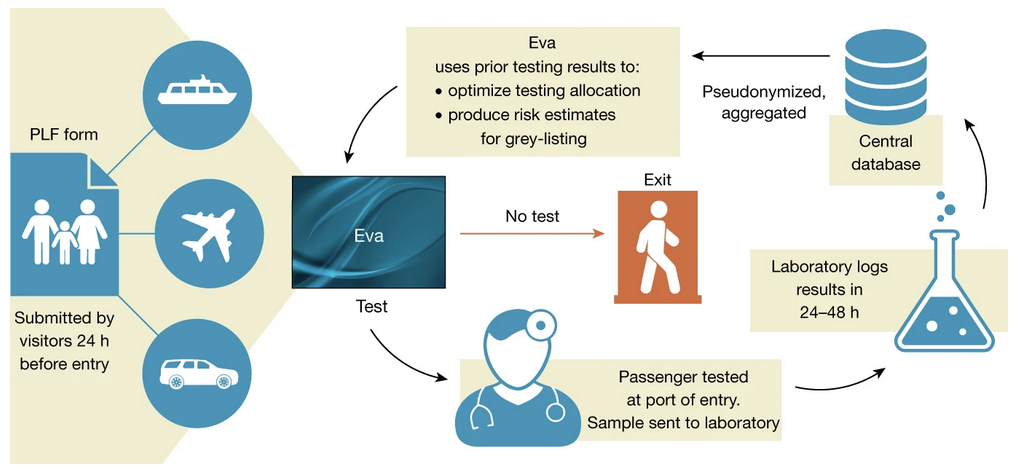

Hamsa demonstrated that bandits can be powerful in practice, even under challenging circumstances. Picture the setting: it is Spring 2020, the pandemic has just started, and in Greece, the tourist season is approaching rapidly. Since tourism accounts for 25% of GDP, Greece literally cannot afford to remain in lockdown and decides to open borders for tourists. How do you keep the public safe when you expect 30k to 100k tourists to arrive every day, while you only have a limited capacity of 8k daily PCR tests that have a 2-day turnover time. Furthermore, the rate of COVID infections flares up in different countries across time so the testing results are only useful for a short period of time before becoming outdated. How can you allocate the limited number of tests in a way that minimizes the number of infected tourists entering the country? Hamsa and team’s answer: use a contextual bandit.

Lo and behold, it worked and the team caught almost twice as many infection than random sampling would have. Hamsa demonstrates there is hope for the practical applicability of bandits, and likely saved affair number of lives in the process.

The full paper is published in Nature.

John Cai on heterogeneous treatment effect estimation

Another big topic at CODE was understanding and estimating heterogeneous treatment effects (HTE), with clear applications in industry illustrated by talks from Snap, Netflix, and Meta. Automatically finding segments of users for whom a treatment works particularly well, or poorly, has clear applications but is also a thorny problem that is far from solved.

John Cai from Snap gave an overview of Snap’s approach to HTE, bridging the gap between theory and practice: first by evaluating the effectiveness of testing whether HTE exist in the first place. If there are no heterogeneous effects, then a reasonable assumption is that the variance of control and treatment are the same. This reduces the problem to testing the hypothesis that the variances are equal.

If we do detect a difference in variances, then we can focus on finding dimensions that contribute most to heterogeneity in treatment effects by decomposing the total treatment effect variation into explained and idiosyncratic variation. All of this was demonstrated using an actual experiment the team ran at Snap.

Wrapping up

It is clear that interest in experimentation is growing rapidly, and we are only scratching the surface on problems practitioners face. In particular, I expect there to be a lot more work on interference, sequential testing, heterogeneous treatment effects, and understanding long term outcomes. But as we nerd out on these problems, we should also keep the UX in mind: we cannot just solve the mathematical problems, we also need to make solutions accessible to the non-expert so they feel empowered to make better decisions.

If you also attended CODE, let me know what your highlights are. If you did not, hopefully this inspires you to visit Boston next year; the weather was surprisingly great!